...A sweep?

It is the five letter word I associate with Turner Field, and the Braves doing it to the Mets. I can't imagine doing it the other way around. But when Kaz Matsui has an eight game hitting streak, anything is possible.

And how about Cliff Floyd for a Gold Glove?

And how about getting some run support for Tom Glavine? I'm happy the guy blanked his ex-team, but still, somebody needs to hit for him at some point.

Sweep? Really?

Sunday, April 30, 2006

Saturday, April 29, 2006

The M&M/W&W Report: On All Cylinders

Being Mets fans, we're trained always look for the negative. But after last night's game and some morning reflection, I can't find anything negative with this big win at Turner Field. Look at the good things that happened:

--Kaz Matsui kept up his offensive and defensive rebirth, especially by saving David Wright another error on a throw to second.

--Pedro Martinez was, well, Pedro-like. Except for the homer by Larry Jones, he was masterful in his duel with John Smoltz.

--David Wright broke out of his slump with two home runs.

--Julio Franco got one of the classiest receptions I've ever seen from Atlanta fans when he pinch hit.

--Billy Wagner's fastball hit 99mph as he got out of a jam to save it in the 9th.

--Jose Reyes and Paul LaDuca did some textbook manufacturing of an extra crucial run in the 9th.

--and finally, Endy Chavez kept making good defensive plays, and avoided the world's largest flying bug during his last at bat.

If Glavine continues his recent resurgence against his old team, this could be a great weekend.

--Kaz Matsui kept up his offensive and defensive rebirth, especially by saving David Wright another error on a throw to second.

--Pedro Martinez was, well, Pedro-like. Except for the homer by Larry Jones, he was masterful in his duel with John Smoltz.

--David Wright broke out of his slump with two home runs.

--Julio Franco got one of the classiest receptions I've ever seen from Atlanta fans when he pinch hit.

--Billy Wagner's fastball hit 99mph as he got out of a jam to save it in the 9th.

--Jose Reyes and Paul LaDuca did some textbook manufacturing of an extra crucial run in the 9th.

--and finally, Endy Chavez kept making good defensive plays, and avoided the world's largest flying bug during his last at bat.

If Glavine continues his recent resurgence against his old team, this could be a great weekend.

Wednesday, April 26, 2006

The M&M Mets/The Wright and Wrong Report: Late Night, Late Afternoon, Late Comebacks

The two games in the past 18 hours have proved to me that perhaps there is something different about this edition of the Mets. They've got guts. Heck, Kaz Matsui got a two hits Tuesday night, and then drove in a run (giving him a hit in every game he's played so far) and made a fine catch Wednesday afternoon, so we all know that this isn't the 2005 Mets. Soon I might even forget Anderson Hernandez. (Probably not, but who knows--I've already forgotten the name of the guy that was supposed to be our starting centerfielder. Supposedly a decision will be made about him on Friday. Why oh why has the front office waited so long to put the 117-million dollar man on the DL?)

Tuesday night Steve Trachsel showed why he should be called the third starter by shutting the Giants down--and challenging Barry Bonds even though the fat old man hit a home run off of him early in the game. I'm still not sure why Willie Randolph pinch hit for Trachsel with Jose "Ofer's Are My Middle Name" Valentin when Trachsel had thrown less than 80 pitches.

Wednesday afternoon's win was--as a co-worker said to me as I started typing this--bittersweet. First, the sweet: they came back three times, finally winning the game in the 11th. Jose Reyes stole some key bases and the 87 year old Julio Franco proved yet again he was worth that dubious two year deal. And how sweet was it to see Barry Bonds' fielding cost the Gioants the game, just a brief time after he tied it with his 710th home run off Billy Wagner. That blown save was not Wagner's fault, it rests on the shoulders of David Wright, who seems to be taking his slump with him onto the field. These throwing errors are starting to get a bit worrysome.

The bitter part of this game was Brian Bannister, who seemed to blow a hamstring trying to score the tie breaking run in the 6th. Losing a starter is something this team could ill aford, especially with a guaranteed loss every time Victor Zambrano pictches. What to do? Aaron Heilman back in the rotation? Jose Lima called up from Triple A? This will be a decision that will have a far reaching impact on the first half of the season. Good thing tomorrow is a day off so the team can ponder these decisions.

4-3 on the road trip so far. Coming out of Atlanta with 6-4 record would be a pleasant surprise.

Tuesday night Steve Trachsel showed why he should be called the third starter by shutting the Giants down--and challenging Barry Bonds even though the fat old man hit a home run off of him early in the game. I'm still not sure why Willie Randolph pinch hit for Trachsel with Jose "Ofer's Are My Middle Name" Valentin when Trachsel had thrown less than 80 pitches.

Wednesday afternoon's win was--as a co-worker said to me as I started typing this--bittersweet. First, the sweet: they came back three times, finally winning the game in the 11th. Jose Reyes stole some key bases and the 87 year old Julio Franco proved yet again he was worth that dubious two year deal. And how sweet was it to see Barry Bonds' fielding cost the Gioants the game, just a brief time after he tied it with his 710th home run off Billy Wagner. That blown save was not Wagner's fault, it rests on the shoulders of David Wright, who seems to be taking his slump with him onto the field. These throwing errors are starting to get a bit worrysome.

The bitter part of this game was Brian Bannister, who seemed to blow a hamstring trying to score the tie breaking run in the 6th. Losing a starter is something this team could ill aford, especially with a guaranteed loss every time Victor Zambrano pictches. What to do? Aaron Heilman back in the rotation? Jose Lima called up from Triple A? This will be a decision that will have a far reaching impact on the first half of the season. Good thing tomorrow is a day off so the team can ponder these decisions.

4-3 on the road trip so far. Coming out of Atlanta with 6-4 record would be a pleasant surprise.

Tuesday, April 25, 2006

The M&M Mets: No No to the No-No

Q: You know what happened at AT&T Park last night?

A: No, what?

Q: Kaz Matsui broke up a no hitter in the 6th inning! But he also botched two defensive plays that cost the Mets 3 runs!

A: Awesome! I knew we'd never miss Anderson Hernandez! Anything else good happen?

Q: Um, no. However, I promise to never make bold statements about Tom Glavine (6 runs in 6 plus innings) ever again.

A: That's a good idea, jackass.

A: No, what?

Q: Kaz Matsui broke up a no hitter in the 6th inning! But he also botched two defensive plays that cost the Mets 3 runs!

A: Awesome! I knew we'd never miss Anderson Hernandez! Anything else good happen?

Q: Um, no. However, I promise to never make bold statements about Tom Glavine (6 runs in 6 plus innings) ever again.

A: That's a good idea, jackass.

Monday, April 24, 2006

The Wright and Wrong/M&M Mets Weekend Report: I Still Hate One Guy...

...Victor Zambrano.

Seriously, when he pitches I always pencil in a loss. The team has gone .500 since its 7-1 start, and I blame Zambrano for all of it with his three starts. I can't believe I'm saying this, but if Jorge "Benitez Jr." Julio continues to improve, perhaps it's time to give Aaron Heilman the 4th starter role, move Julio into tighter game situations and DFA Zambrano. He's not going to get better. Everyone knows it. Admit the Kazmir trade was a big debacle and move on.

Other weekend thoughts:

--The 14 inning loss overshadowed one thing--this bullpen held up for a long time. I grow more confident about all the minor parts (Bradford, Oliver, Feliciano).

--Keith Hernandez might want to control himself once in a while. And not call Pedro Feliciano "Jose."

--The 2006 edition of Pedro Martinez is pitching like, well, the 2005 Pedro, except with solid bullpen help for once. Winning 20 games seems like a possibility, and hopefully Pedro won't get wore down by the stretch run.

--Kaz Matsui's inside the park job seems like a long time ago after his striking out with the bases loaded during Sunday's game. He better get hot by the time the Mets are back at Shea, or he's going to be in for it.

--David Wright seems to be working his way out of his mini-slump. I predict a big series from him at Pac Bell, or whatever they call it nowadays.

Road trip continues tonight in San Fran, and I think it's going to be another great start from Tom Glavine. 2 out of 3 would give the team a winning road trip heading into Atlanta, which is key, because we all know that they won't win that series unless Atlanta fields a team with Bobby Cox batting clean-up.

Seriously, when he pitches I always pencil in a loss. The team has gone .500 since its 7-1 start, and I blame Zambrano for all of it with his three starts. I can't believe I'm saying this, but if Jorge "Benitez Jr." Julio continues to improve, perhaps it's time to give Aaron Heilman the 4th starter role, move Julio into tighter game situations and DFA Zambrano. He's not going to get better. Everyone knows it. Admit the Kazmir trade was a big debacle and move on.

Other weekend thoughts:

--The 14 inning loss overshadowed one thing--this bullpen held up for a long time. I grow more confident about all the minor parts (Bradford, Oliver, Feliciano).

--Keith Hernandez might want to control himself once in a while. And not call Pedro Feliciano "Jose."

--The 2006 edition of Pedro Martinez is pitching like, well, the 2005 Pedro, except with solid bullpen help for once. Winning 20 games seems like a possibility, and hopefully Pedro won't get wore down by the stretch run.

--Kaz Matsui's inside the park job seems like a long time ago after his striking out with the bases loaded during Sunday's game. He better get hot by the time the Mets are back at Shea, or he's going to be in for it.

--David Wright seems to be working his way out of his mini-slump. I predict a big series from him at Pac Bell, or whatever they call it nowadays.

Road trip continues tonight in San Fran, and I think it's going to be another great start from Tom Glavine. 2 out of 3 would give the team a winning road trip heading into Atlanta, which is key, because we all know that they won't win that series unless Atlanta fields a team with Bobby Cox batting clean-up.

Friday, April 21, 2006

The M&M Mets: Um, Welcome Back!

An inside-the-park homer run?

Turning in a way above average double play with the bases loaded?

Um, who is this Kaz Matsui, and why does he only come out during his first game of the season?

And congrats to Julio Franco, who became the oldest player to ever hit a home run. Who thought 67 year olds could play that well?

Turning in a way above average double play with the bases loaded?

Um, who is this Kaz Matsui, and why does he only come out during his first game of the season?

And congrats to Julio Franco, who became the oldest player to ever hit a home run. Who thought 67 year olds could play that well?

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

The Wright And Wrong Report: Uh-Oh

It's official--David Wright is in a slump. O-for-the series against Atlanta is bad. All of sudden I'm getting memories of 2005 coming back in--choking against the Braves, half the lineup out with injuries, etc. The high of last Monday seems long ago. The only plus out of today's 2-1 defeat is that once again Tom Glavine pitched like Tom Glavine. Alas, he still can't beat his old team.

Massive West Coast trip on tap over the next 11 days. I could see this team coming back at the .500 mark if some folks don't heal and break their slumps.

Massive West Coast trip on tap over the next 11 days. I could see this team coming back at the .500 mark if some folks don't heal and break their slumps.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

The Wright and Wrong Report: Ah, the Comfort of Defeat

First things first: Victor Zambrano did not cost the Mets tonight’s game. Braves pitcher Kyle Davies won it. He was masterful in giving up three hits in his complete game 7-1 triumph.

That being said, when will Mets upper management realize that Victor Zambramo is a bust—and having him between Pedro and Glavine in the rotation assures no three game winning streaks. I know someone up there doesn’t want to admit defeat in the legendary Scott Kazmir steal (thanks for that one Al Leiter), but seriously, it’s time to give it up.

Unfortunately (with Floyd and Beltran out) David Wright is getting into a bit of a mini-slump, punctuated during his last at bat where he smashed his piece of lumber into the ground in disgust. The 23 year old Wright will come around—the 30 year old Zambrano never will. And the Mets can count on having an assured loss every time he pitches. "Zambrano's Time, Losing Team" should be a song a marketing company can write.

I predicted 2 out of 3 for this series—I’ll be happy with that if Tom Glavine’s hot streak continues.

That being said, when will Mets upper management realize that Victor Zambramo is a bust—and having him between Pedro and Glavine in the rotation assures no three game winning streaks. I know someone up there doesn’t want to admit defeat in the legendary Scott Kazmir steal (thanks for that one Al Leiter), but seriously, it’s time to give it up.

Unfortunately (with Floyd and Beltran out) David Wright is getting into a bit of a mini-slump, punctuated during his last at bat where he smashed his piece of lumber into the ground in disgust. The 23 year old Wright will come around—the 30 year old Zambrano never will. And the Mets can count on having an assured loss every time he pitches. "Zambrano's Time, Losing Team" should be a song a marketing company can write.

I predicted 2 out of 3 for this series—I’ll be happy with that if Tom Glavine’s hot streak continues.

Who's that Other Guy?

If you're a regular reader of the Zisk blog, you might be wondering, "Who the heck is Throm Sturmond, and why is he writing here?"

Well, Throm is a Cubs fan (we don't hold that against him) who wrote for Zisk #12--and is currently in Hong Kong working as a journalist. When he offered to blog his attempts to watch his team from half a world away, Mike and I couldn't resist. So you'll see periodic updates from him on his (so far) quixotic quest.

Next stop for Zisk, Mars, Rickey Henderson's home planet.

Well, Throm is a Cubs fan (we don't hold that against him) who wrote for Zisk #12--and is currently in Hong Kong working as a journalist. When he offered to blog his attempts to watch his team from half a world away, Mike and I couldn't resist. So you'll see periodic updates from him on his (so far) quixotic quest.

Next stop for Zisk, Mars, Rickey Henderson's home planet.

Monday, April 17, 2006

The M&M Mets: Pedro’s Record - And a Horrible Record

200 wins.

You know, there have been times that it took the Mets three seasons to total up that many wins. And now Pedro Martinez has reached that milestone. You could feel the electricity through the TV from Shea every time Pedro got to two strikes. Hell, it felt like September baseball against the Braves tonight, and even though Pedro isn’t into mid-season form yet, it’s obvious that this man knows how to rise to the occasion. It wasn’t a perfect 6 and 2/3 innings, but it didn’t need to be with the growing in stature every day bullpen combo of Duaner Sanchez and Billy Wagner. This is a game last year that Pedro would have left with a lead and someone would have blown it. Not this year.

(Hang on, let me go crack a beer in celebration. Ah, that’s better.)

10-2. Still the best Mets start ever. The first time any team has opened a 5 game lead in just 12 games, EVER. I haven’t felt this positive about the Mets since they beat St. Louis in the NLCS in 2000. But there’s something different about this team than the Leiter-Piazza-Alfonzo era. There’s a confidence, something intangible I get from watching these guys play. It’s that swagger and playfulness that Pedro had all last season that seems to have infected the rest of the team now. David Wright has his first off night (5 runs stranded)? No problem, Xavier Nady will get 3 hits and drive in 2. Carlos Beltran out with a hamstring issue? Carlos Delgado just about breaks the right field scoreboard with a 2 run shot.

And now being a Mets fan, I must look for the dark lining--besides Cliff Floyd injuring his rib cage tonight.

Hmmmmm….

(Still thinking…)

Oh, yeah, Kaz Matsui is almost done with rehab, and he’ll be back on the roster soon. This can bring nothing but bad karma. And speaking of bad, check out the new Mets theme song: "Our Team Our Time."

I’m sorry, but this is even worse than the 1986 vintage "Let’s Go Mets." The production for "Our Team Our Time" might have been hip in 1990, but not in 2006. Only someone that works for a hundred-million-dollar company would think this song was worth bringing to the general public. If the Mets collapse after this great start, I will blame this song and find the jackasses that did it.

Oh, and Victor Zambrano goes tomorrow night, so I’ll still take 10-3.

Yeah, I don't know how to enjoy success.

You know, there have been times that it took the Mets three seasons to total up that many wins. And now Pedro Martinez has reached that milestone. You could feel the electricity through the TV from Shea every time Pedro got to two strikes. Hell, it felt like September baseball against the Braves tonight, and even though Pedro isn’t into mid-season form yet, it’s obvious that this man knows how to rise to the occasion. It wasn’t a perfect 6 and 2/3 innings, but it didn’t need to be with the growing in stature every day bullpen combo of Duaner Sanchez and Billy Wagner. This is a game last year that Pedro would have left with a lead and someone would have blown it. Not this year.

(Hang on, let me go crack a beer in celebration. Ah, that’s better.)

10-2. Still the best Mets start ever. The first time any team has opened a 5 game lead in just 12 games, EVER. I haven’t felt this positive about the Mets since they beat St. Louis in the NLCS in 2000. But there’s something different about this team than the Leiter-Piazza-Alfonzo era. There’s a confidence, something intangible I get from watching these guys play. It’s that swagger and playfulness that Pedro had all last season that seems to have infected the rest of the team now. David Wright has his first off night (5 runs stranded)? No problem, Xavier Nady will get 3 hits and drive in 2. Carlos Beltran out with a hamstring issue? Carlos Delgado just about breaks the right field scoreboard with a 2 run shot.

And now being a Mets fan, I must look for the dark lining--besides Cliff Floyd injuring his rib cage tonight.

Hmmmmm….

(Still thinking…)

Oh, yeah, Kaz Matsui is almost done with rehab, and he’ll be back on the roster soon. This can bring nothing but bad karma. And speaking of bad, check out the new Mets theme song: "Our Team Our Time."

I’m sorry, but this is even worse than the 1986 vintage "Let’s Go Mets." The production for "Our Team Our Time" might have been hip in 1990, but not in 2006. Only someone that works for a hundred-million-dollar company would think this song was worth bringing to the general public. If the Mets collapse after this great start, I will blame this song and find the jackasses that did it.

Oh, and Victor Zambrano goes tomorrow night, so I’ll still take 10-3.

Yeah, I don't know how to enjoy success.

TWIB Report: This Webcast is Balky

At this point, I was hoping to post a couple observations to Zisk about my beloved Cubs. While I had to give up my Cubs seasons tickets last fall for my new job in Hong Kong, I had high hopes about MLB's webcasts. A full season of nearly-live broadcasts, be it TV or radio, would stream into my apartment as I pedal away on my bike that's hooked up to a stationary trainer. If I couldn't enjoy Matt Murton's first full season in the bigs, Aramis Ramirez's mashing uppercuts and Derrek Lee's quest to prove he's for real - I swear, last season wasn't a hoax - I could at least follow them on the web.

Well, remember, this is something coming out of an office overseen by Bud Selig. On my Mac, the video starts, stops and sputters ever 3-4 seconds, rendering it unwatchable. Even the radio feed is jittery. Arrgh! Radio, which even the smallest public radio station can stream over the web pretty much flawlessly, but MLB apparently can't at least on my Mac.

I'm trying to get my Dell PC networked this week, so I can stream stuff through there, and hopefully all will be better. But please, if anyone sees Bud Selig this week, please throw your Ibook, your Ipod or any other Apple product at him for me. Not too hard, just enough to draw his attention. That's all I can ask.

Well, remember, this is something coming out of an office overseen by Bud Selig. On my Mac, the video starts, stops and sputters ever 3-4 seconds, rendering it unwatchable. Even the radio feed is jittery. Arrgh! Radio, which even the smallest public radio station can stream over the web pretty much flawlessly, but MLB apparently can't at least on my Mac.

I'm trying to get my Dell PC networked this week, so I can stream stuff through there, and hopefully all will be better. But please, if anyone sees Bud Selig this week, please throw your Ibook, your Ipod or any other Apple product at him for me. Not too hard, just enough to draw his attention. That's all I can ask.

The Wright and Wrong Report: Zambrano, Get Away From Bannister!

WFAN's Howie Rose summed it up best during the 5th inning of yesterday's game: "Brian Bannister's start today has been Zambrano-like." Lots of walks, bases-loaded twice, my head ready to explode from the stress--yup, it was just like every time Victor touches the ball. Yet there was a difference, a very big one. This Bannister kid gets out of these jams, and doesn't get"The Victor Face" when he has to do it. 5 innings and almost 110 pitches--hell, that's Leiter-esque. The game included another ho-hum day for David Wright, 2 for 4, 2 runs scored, still batting way over .400.

9-2. Best start in Mets history. Yet if the Mets are swept by the Braves over the next three games, it will mean nothing. If they win Pedro's and Glavine's starts (I already know Zambrano is a loss Tuesday), 2 out of 3 will put them 6 games up on the Braves already. If they win all three, then I might believe that this start is not a mirage.

And oh, I so want to believe. I really do.

9-2. Best start in Mets history. Yet if the Mets are swept by the Braves over the next three games, it will mean nothing. If they win Pedro's and Glavine's starts (I already know Zambrano is a loss Tuesday), 2 out of 3 will put them 6 games up on the Braves already. If they win all three, then I might believe that this start is not a mirage.

And oh, I so want to believe. I really do.

Sunday, April 16, 2006

Making Perry Proud, or Accentuating the Positive

My wife, six months pregnant, has entered the stage where she can see movement as well as feel it. It's amazing, or so I hear. Everytime she puts my hand to her belly, junior stops stirring. It's disappointing--I want to witness what I'm hearing so much about, afterall--but I try to put a positive spin on the situation, telling myself that junior's inactivity is due to my calming effect.

On a different scale, the same goes for the Mets. I've heard a lot about this 2006 Mets team--the impressive balance of hitting, pitching, and defense; the swagger that emerges with an 8-1 start--but prior to yesterday I hadn't been able to watch one of the games. Then my friend Jake called with an extra ticket to Saturday's day game against the Brewers. Steve Trachsel vs. Nationals castoff Tomo Ohka. This was a game an 8-1 team should win, I thought as the 7 train wound its way through Queens. Turned out to be a game where an 8-1 team got thumped 8-2.

Trachsel was flat, coughing up four runs over five innings. Cliff Floyd was dogging it in left. Beltran and Nady misjudged routine line drives in center and right, respectively. Wright looked overly aggressive, twice swinging at the first pitch with runners on base. And then there was the bullpen. Darren Oliver and Chad Bradford were all right, combining for one earned run over three innings, but in between their stints came Jorge Julio, he of 16.88 ERA. The only good thing about such a zeppelin-like ERA is that it's nearly impossible to raise such a stat. Plunking the leadoff hitter, as Julio did in top of the eighth, certainly helps. By the time Geoff Jenkins clubbed a 3-run homerun off the rightfield scoreboard, Julio had succeeded in raising his ERA to 19.64 (causing Omar Minaya to order one of his lackeys to check out cheaptickets.com for flights to Norfolk).

It wasn't just on the field where it felt like the Art Howe era, though. The fans were restless but inattentive. Sure, they booed Jorge Julio on cue ("Bring Back Benson!"), but it seemed like most of the energy flowing from the stands was spent critiquing various attempts at the wave (booing a wave that stalled out in the bottom of the sixth, for example, which may have been due to the fact that it was a 4-1 game and Wright was coming to the plate with Beltran already perched on second). I was waiting for a beachball to rear its ugly rainbow colored head.

But Jake, a White Sox fan in town from Chicago, was all about focusing on other elements of the game--the beautiful 80 degree day, the pinch hitting attempts by Julio Franco and Jose Valetin (the man whose moustache restored Jake's faith in baseball), the hitting display put on by the Brewers' Prince Fielder. My guess is that some of Jake's enthusiasm stems from the fact that his ChiSox are defending champs, but regardless, it's all about looking for the positives and if this was the 2006 Mets at their worst, we're in for a great summer.

On a different scale, the same goes for the Mets. I've heard a lot about this 2006 Mets team--the impressive balance of hitting, pitching, and defense; the swagger that emerges with an 8-1 start--but prior to yesterday I hadn't been able to watch one of the games. Then my friend Jake called with an extra ticket to Saturday's day game against the Brewers. Steve Trachsel vs. Nationals castoff Tomo Ohka. This was a game an 8-1 team should win, I thought as the 7 train wound its way through Queens. Turned out to be a game where an 8-1 team got thumped 8-2.

Trachsel was flat, coughing up four runs over five innings. Cliff Floyd was dogging it in left. Beltran and Nady misjudged routine line drives in center and right, respectively. Wright looked overly aggressive, twice swinging at the first pitch with runners on base. And then there was the bullpen. Darren Oliver and Chad Bradford were all right, combining for one earned run over three innings, but in between their stints came Jorge Julio, he of 16.88 ERA. The only good thing about such a zeppelin-like ERA is that it's nearly impossible to raise such a stat. Plunking the leadoff hitter, as Julio did in top of the eighth, certainly helps. By the time Geoff Jenkins clubbed a 3-run homerun off the rightfield scoreboard, Julio had succeeded in raising his ERA to 19.64 (causing Omar Minaya to order one of his lackeys to check out cheaptickets.com for flights to Norfolk).

It wasn't just on the field where it felt like the Art Howe era, though. The fans were restless but inattentive. Sure, they booed Jorge Julio on cue ("Bring Back Benson!"), but it seemed like most of the energy flowing from the stands was spent critiquing various attempts at the wave (booing a wave that stalled out in the bottom of the sixth, for example, which may have been due to the fact that it was a 4-1 game and Wright was coming to the plate with Beltran already perched on second). I was waiting for a beachball to rear its ugly rainbow colored head.

But Jake, a White Sox fan in town from Chicago, was all about focusing on other elements of the game--the beautiful 80 degree day, the pinch hitting attempts by Julio Franco and Jose Valetin (the man whose moustache restored Jake's faith in baseball), the hitting display put on by the Brewers' Prince Fielder. My guess is that some of Jake's enthusiasm stems from the fact that his ChiSox are defending champs, but regardless, it's all about looking for the positives and if this was the 2006 Mets at their worst, we're in for a great summer.

Saturday, April 15, 2006

The Wright and Wrong Report: Can't Be Perfect All the Time

Oh, well, David Wright couldn’t hit in every game of the season. Yet the Mets still won, in a nail-biter of a game that last year I have no doubt they would have lost.

Best start (8-1) since 1985--when do I start getting nervous that something bad is about to happen? I mean, I am a Mets fan, we always look for the worst in our team.

Best start (8-1) since 1985--when do I start getting nervous that something bad is about to happen? I mean, I am a Mets fan, we always look for the worst in our team.

Thursday, April 13, 2006

The Wright And Wrong Report: Let's Take Some Extra BP

Overheard in the visitor’s locker room before today’s Mets-Nationals game at RFK Stadium in D.C.

Carlos Beltran: (Looking at starting lineup) So I see Victor Zambrano is pitching today…

Carlos Delgado: (Looking up from his pitcher’s chart book) Yup, his first start of the year.

Cliff Floyd: I wonder how it’s going to pan out? Z had some rough times for us at the end of last season.

David Wright: You know how we can make sure nobody notices how he pitches?

Beltran: How?

Wright: Let’s all hit home runs and score at least 10. Then he’ll be relaxed and the bullpen will have a nice lead to work with when they have to bail Victor out, because you know they will.

All: Agreed!

This first seven minutes of this 13-4 Mets win were beautiful to watch, as everyone took Wright’s advice to heart and hit the ball as if they were taking batting practice in Coors field. Beltran got it rolling with another huge blow, but our man David really got things rolling with his 2 run jack. So Wright’s 8 game hitting streak is intact, and now he’s got a new RBI streak to start. He’s got 12 ribbies already and is batting .469, putting him in the Top 5 in the NL in both categories. This 7-1 start ties the Mets best start since 1985 and is the best record in the major leagues, and this current six game winning streak matches last year’s best streak. But it’s not yet time to get excited--most of these wins have come at the expense of the Nationals, who seemed destined to battle Florida for last. The next six games at home are the first true test of the year--the much improved Brewers and the evil Braves will be at Shea, and they’re not going to be pushovers.

Okay, now for the first Wrong report of the year. The best thing that cane be said about Victor Zambrano’s start is, um, well, he kept the team in the game. No, that’s not it. How about, he lasted 5 innings, which set up the bullpen perfectly to hold the 7-3 lead? Yeah, perfect. Zambrano 2006 looked just like Zambrano 2005--breezing through an inning or two, teasing us with his talent. Next thing you know, I look up from my desk at work and he’s got two guys on and he’s doing what I like to call “The Victor Grimace.” It’s when Zambrano’s face scrunches up and he takes his hat off, wipes his brow, and wishes his buddy Rick Peterson would pay him a visit. We certainly can’t expect the Mets to score 13 runs in every one of his starts, so I expect Wednesday’s day game against the Braves to be filled with boos after 3 innings. Especially if Jorge “I gave up a home run in my one inning and my ERA still went down by 6” Julio pitches in the same game.

Just to end on a positive pitching note, Darren Oliver looked really good in his two innings--and he made the Nats pay with his bases-loaded single. This bullpen might be better than we could have hoped for.

Carlos Beltran: (Looking at starting lineup) So I see Victor Zambrano is pitching today…

Carlos Delgado: (Looking up from his pitcher’s chart book) Yup, his first start of the year.

Cliff Floyd: I wonder how it’s going to pan out? Z had some rough times for us at the end of last season.

David Wright: You know how we can make sure nobody notices how he pitches?

Beltran: How?

Wright: Let’s all hit home runs and score at least 10. Then he’ll be relaxed and the bullpen will have a nice lead to work with when they have to bail Victor out, because you know they will.

All: Agreed!

This first seven minutes of this 13-4 Mets win were beautiful to watch, as everyone took Wright’s advice to heart and hit the ball as if they were taking batting practice in Coors field. Beltran got it rolling with another huge blow, but our man David really got things rolling with his 2 run jack. So Wright’s 8 game hitting streak is intact, and now he’s got a new RBI streak to start. He’s got 12 ribbies already and is batting .469, putting him in the Top 5 in the NL in both categories. This 7-1 start ties the Mets best start since 1985 and is the best record in the major leagues, and this current six game winning streak matches last year’s best streak. But it’s not yet time to get excited--most of these wins have come at the expense of the Nationals, who seemed destined to battle Florida for last. The next six games at home are the first true test of the year--the much improved Brewers and the evil Braves will be at Shea, and they’re not going to be pushovers.

Okay, now for the first Wrong report of the year. The best thing that cane be said about Victor Zambrano’s start is, um, well, he kept the team in the game. No, that’s not it. How about, he lasted 5 innings, which set up the bullpen perfectly to hold the 7-3 lead? Yeah, perfect. Zambrano 2006 looked just like Zambrano 2005--breezing through an inning or two, teasing us with his talent. Next thing you know, I look up from my desk at work and he’s got two guys on and he’s doing what I like to call “The Victor Grimace.” It’s when Zambrano’s face scrunches up and he takes his hat off, wipes his brow, and wishes his buddy Rick Peterson would pay him a visit. We certainly can’t expect the Mets to score 13 runs in every one of his starts, so I expect Wednesday’s day game against the Braves to be filled with boos after 3 innings. Especially if Jorge “I gave up a home run in my one inning and my ERA still went down by 6” Julio pitches in the same game.

Just to end on a positive pitching note, Darren Oliver looked really good in his two innings--and he made the Nats pay with his bases-loaded single. This bullpen might be better than we could have hoped for.

The M&M Mets: Who Needs to Pitch Inside?

So at the begining of the week Major League Baseball warned both the Mets and the Nationals about throwing at each other's hitters. Before last night's game at RFK, Pedro Martinez must have thought to himself, "Well then, if you don't want me to pitch inside, I'll just get all these guys out by using the outside corner--and that spacious centerfield." And that's just what he did. Jose Guillen had nothing to get upset about (well, except grounding into the well executed double play that got Pedro out of a bses-loaded jam). And Carlos Beltran got a workout with all the fly balls to center. (I think at least 8?) Overall, Pedro didn't have his top fastball, but he looked a whole lot more comfortable than his first start.

Oh, and remember that Kaz Matsui guy? Well, he might never come back from rehab in Florida if Willie Randolph has his way, just from what I've gathered listening to Gary Cohen on SNY (don't mean to rub it in Mike) and a lengthy discussion Richard Neer had about second base last night on WFAN. (By the way, Richard Neer is perhaps the most intelligent man in sports talk today. I wish he was on more.) It seems Randolph has had his fill of Matsui, and if Anderson Hernandez hits .240 the next two months, he and his great defense aren't going anywhere.

Oh, and remember that Kaz Matsui guy? Well, he might never come back from rehab in Florida if Willie Randolph has his way, just from what I've gathered listening to Gary Cohen on SNY (don't mean to rub it in Mike) and a lengthy discussion Richard Neer had about second base last night on WFAN. (By the way, Richard Neer is perhaps the most intelligent man in sports talk today. I wish he was on more.) It seems Randolph has had his fill of Matsui, and if Anderson Hernandez hits .240 the next two months, he and his great defense aren't going anywhere.

The Wright and Wrong Report: Watch Out Jose Reyes...

...David Wright now has as many triples (2) as you do after last night's game. But it was an off night for our 3rd baseman, as he didn't drive in a run for the first time this season. I guess we'll have to settle for him going 2-for-4 with the aforementioned triple, and once again led some very solid infield defense. The team's defense was certainly the key in the Mets 3 to 1 win--the double play with the bases loaded in the 6th was a thing of beauty, highlighted by the amazing spin-n-split of Anderson Hernandez.

Wright to Reyes to Hernandez--I think that's a combo I could watch for a decade.

Alas, today the five game winning streak will likely end with Victor Zambrano's first game of the year. I'm almost to afraid to put the game on at work--I might hurt my back more by yelling at the 6 walks we're bound to see.

Wright to Reyes to Hernandez--I think that's a combo I could watch for a decade.

Alas, today the five game winning streak will likely end with Victor Zambrano's first game of the year. I'm almost to afraid to put the game on at work--I might hurt my back more by yelling at the 6 walks we're bound to see.

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

And Now for Something Slightly Different

I live in Putnam County, north of NYC, and televised Mets games have been blacked out of the entire county, treated with all the warmth of a Sandanista in the Reagan White House. Last Friday, desperate to unwind from the week by watching the Mets take on the Marlins, I called every bar in the area. I searched for one joint with a satellite dish. No luck. "The Mets have been blacked out of Putnam County," the bartender at Boomers told me.

I've tried to pick up games on WFAN, but radio reception in our apartment is painfully saturated with static. Meanwhile, on TV, we've been treated to a number of quality of programs in place of Mets games. On Thursday night, when the Mets/Nationals game was blacked out on ESPN, we got a halfhearted debate about the recently released 2006 NFL schedule. (No one--not Michael Vick, not any one of the Super Bowl champion Steelers, no one--cares about the NFL schedule in April. Not even the ESPN sports geeks could feign interest.) On Friday night, channel 9 replaced the game with an episode of "Will and Grace." It was the one where you think, if only for a moment, that Will is going to ditch that pesky homosexuality and finally get together with Grace, all while their friends sprinkle in catty comments. Classic. Saturday, however, was the clincher. Again, no Mets game. Instead an infomercial for a Dual Action Colon Cleansing program. I take the couch in hopes of a Tom Glavine/Dontrelle Willis showdown and find instead why I really need an all-natural pipe cleaning routine. Spring is the time of renewal and birds chirping and the invigorating feeling of sunlight on your cheeks as you walk out the door from work and, for those who pay $40 for cable TV each month, it is also the time when it is your right to watch the motherlovin' Mets each night. The bell tolls for those denied SNY.

I've tried to pick up games on WFAN, but radio reception in our apartment is painfully saturated with static. Meanwhile, on TV, we've been treated to a number of quality of programs in place of Mets games. On Thursday night, when the Mets/Nationals game was blacked out on ESPN, we got a halfhearted debate about the recently released 2006 NFL schedule. (No one--not Michael Vick, not any one of the Super Bowl champion Steelers, no one--cares about the NFL schedule in April. Not even the ESPN sports geeks could feign interest.) On Friday night, channel 9 replaced the game with an episode of "Will and Grace." It was the one where you think, if only for a moment, that Will is going to ditch that pesky homosexuality and finally get together with Grace, all while their friends sprinkle in catty comments. Classic. Saturday, however, was the clincher. Again, no Mets game. Instead an infomercial for a Dual Action Colon Cleansing program. I take the couch in hopes of a Tom Glavine/Dontrelle Willis showdown and find instead why I really need an all-natural pipe cleaning routine. Spring is the time of renewal and birds chirping and the invigorating feeling of sunlight on your cheeks as you walk out the door from work and, for those who pay $40 for cable TV each month, it is also the time when it is your right to watch the motherlovin' Mets each night. The bell tolls for those denied SNY.

The Greatest Video Game Ever

I know that this is spreading on the 'net like wildfire today, but I couldn't resist. If you're a baseball fan, and a fan of '80s video games AND of the Mets, these 8 minutes and 39 seconds will blow your mind.

Who remembered that Marty Barrett was the player of the game?

Who remembered that Marty Barrett was the player of the game?

The Wright and Wrong Report: The Teammates Join In!

Our man David drove in yet another run today--in fact, it was the 4th Mets run in a row he drove in. Finally the rest of the team--even starting pitcher Brian Bannister--decided to get into the act in the 7-1 pounding of the Nationals. Carlos Beltran even hit a home run that I think went over the Washington Monument. Of course, these wins over the Nationals are what a team favored to make it to the playoffs must do to the subpar teams in their own division. It's the home series with Milwaukee and (shudder) Atlanta starting Friday that will be the first true test of these 2006 Mets.

Also worth checking out today: a fun Wright Q&A on the Mets blog done by New York Daily News beat writer Adam Rubin. Rubin has also written a great book about the 2005 Mets called Pedro, Carlos, and Omar : The Story of a Season in the Big Apple and the Pursuit of Baseball's Top Latino Stars. It's a perfect book for communting, as you can get a couple of chapters done during a 45 minute train ride.

Also worth checking out today: a fun Wright Q&A on the Mets blog done by New York Daily News beat writer Adam Rubin. Rubin has also written a great book about the 2005 Mets called Pedro, Carlos, and Omar : The Story of a Season in the Big Apple and the Pursuit of Baseball's Top Latino Stars. It's a perfect book for communting, as you can get a couple of chapters done during a 45 minute train ride.

Monday, April 10, 2006

The Wright and Wrong Report: What Can't This Guy Do?

So the Mets win 3 to 2 over the minor league Marlins, and David Wright drives in all three runs. Seriously, these folks chanting "M-V-P! M-V-P!" at Shea might have something. Watching Wright bat with two strikes in the 7th yesterday, I wasn't uncomfortable. I wasn't tense. I thought to myself, "This guy is going to drive these two runs in." And sure enough, he found a way to do it. Now I don't expect Wright to drive in a run every single game, and I know it's only 5 games so far, but I've just got a different feeling about this team.

Of course, that could change once the first series with the Braves starts next week.

And here's something cool--David Wright has his own blog!

PS: Mike won't be posting that much on the blog the first month or so, since he can't see the damn games! The cable outfit he has up there in the burbs is in the middle being sold to Comcast. Once that sale goes through, SNY will be on his cable and he'll be back up to speed. So I'll also be writing the entries for Pedro's starts until further notice.

Of course, that could change once the first series with the Braves starts next week.

And here's something cool--David Wright has his own blog!

PS: Mike won't be posting that much on the blog the first month or so, since he can't see the damn games! The cable outfit he has up there in the burbs is in the middle being sold to Comcast. Once that sale goes through, SNY will be on his cable and he'll be back up to speed. So I'll also be writing the entries for Pedro's starts until further notice.

Sunday, April 09, 2006

The Wright and Wrong Report: Watching Makes You Late

Friday night was the first occurance of what I'd like to call the "Wright Seat Effect." I was at Jimmy's Corner in midtown Manhattan watching the Mets take on the Marlins, and I had to leave aat 8:40 to be at Town Hall by 8:45. But when I realized that David Wright would be coming up in the bottom half of the inning, I had to text my friend Moria and say I would be late. I had a gut feeling David Wright was due for a homer--and sure enough he was. Fans chanting "MVP, MVP, MVP" was a little too early, but who knows if the Mets keep winning.

Yesterday's rainout pushed back Victor Zambrano's first start of the season, which might mean he'll make his first start on the road. And that is a very good idea.

Yesterday's rainout pushed back Victor Zambrano's first start of the season, which might mean he'll make his first start on the road. And that is a very good idea.

Friday, April 07, 2006

The Wright and Wrong Report: Don't Mess With the 3B

I'd write a whole lot more about the crazy night the Mets and Pedro Martinez had during last night's 10-5 win over the Nationals, but since Mike picked Pedro when we started this year's blog experiment, I'll let him put it in his own words when he checks in. But man, I can't remember a third game of a season being so absolutely insane. 3 hours and 30 minutes which included 5 hit batsmen; one bat-wielding mound charger; both bullpens jogging to the first base line; a 69 year old first basemen playing peacekeeper (and making the most overpaid centerfielder in all of baseball take the dugout steps for a curtain call); an injured umpire causing a game to be delayed 20 minutes; and--perhaps most importantly--finding out that "Mr. Hit Me," Ron Hunt, caused Keith Hernandez to never drink Kahlua again after spring training of his rookie year.

Whew.

And there in the middle of beanball war was The Mets third baseman, dodging two way inside pitches from Ramon Ortiz. I think the lesson that the National League should learn is this: don't mess with David Wright. After those pitches, Wright calmly lined a base hit to keep the Mets offense rolling. 3 for 4, 1 RBI, 2 runs--those are stats Mets fans can enjoy, even with all the craziness.

Oh, and I don't want to forget Mr. Wrong--Victor Zambrano is on track to start Sunday's game. I'll be cleaning my handgun this weekend just so I can shoot my TV when he walks his third batter in an inning.

Whew.

And there in the middle of beanball war was The Mets third baseman, dodging two way inside pitches from Ramon Ortiz. I think the lesson that the National League should learn is this: don't mess with David Wright. After those pitches, Wright calmly lined a base hit to keep the Mets offense rolling. 3 for 4, 1 RBI, 2 runs--those are stats Mets fans can enjoy, even with all the craziness.

Oh, and I don't want to forget Mr. Wrong--Victor Zambrano is on track to start Sunday's game. I'll be cleaning my handgun this weekend just so I can shoot my TV when he walks his third batter in an inning.

Wednesday, April 05, 2006

The Wright and Wrong Report: Is Victor the bullpen coach?

Victor Zambrano, you just might have caught a break. No longer will you be the worst guy on the 2006 Mets who came via trade. After tonight’s implosion by Jorge Julio (who the Mets received when they dumped the Bensons) fans will likely have a new whipping boy. Victor will be able to hold his head high--at least until he starts on Sunday.

David Wright delivered an RBI early in the game, but came up short when the team was down 5 runs in the 10th but had two guys on and nobody out. And you could tell Wright was pissed he didn’t at least get one guy home. The expression on his face when he got back to the dugout said it all

Oy, this could be another long season if Zambrano (and a hint of Looper) infects the Mets bullpen.

David Wright delivered an RBI early in the game, but came up short when the team was down 5 runs in the 10th but had two guys on and nobody out. And you could tell Wright was pissed he didn’t at least get one guy home. The expression on his face when he got back to the dugout said it all

Oy, this could be another long season if Zambrano (and a hint of Looper) infects the Mets bullpen.

Tuesday, April 04, 2006

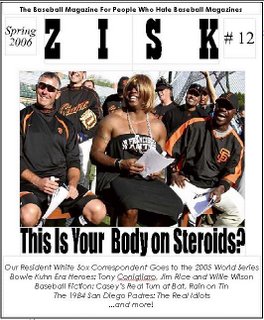

Zisk # 12 is on the way!

Just to let you blog readers know that Zisk issue # 12 is being mailed out as we speak! Everyone should have their copy within a week to 10 days.

Also, one of our veteran writers Jeff Herz has started his own baseball blog. It's definitely worth a read.

Also, one of our veteran writers Jeff Herz has started his own baseball blog. It's definitely worth a read.

Zisk # 12

Publisher’s Note:

Our good friend Mike is a renown wine connoisseur. His refrigerated wine cellar is stocked with his favorite reds (he keeps whites on hand only for close friends). His credentials are impressive—he judges at the Villenave-de-Rions Wine Festival and contributes to California Wine Maker—but what’s most impressive is his wealth of knowledge of all wines; the ones he loves and the ones he loathes, he knows them all. Makes sense, right? Civil war historians don’t just study the people they admire, they cover both sides of the conflict—this is what separates the historian from the re-enactor.

We here at Zisk are forever in search of new ways to deepen our appreciation for the national pastime and more specifically our beloved hometown Mets. Last year on the Zisk website, we blogged (yes, we’re thinking it’s now a verb) the exploits of that 83-79 team each day. We learned a lot about those Mets—it was our very own 162-day afterschool special.

But how to top ourselves? How to maintain our creative interest while still pleasing our audience? Well, taking a page from the David Bowie/Madonna book of career reinvention: we fake English accents, put moles on our cheeks, and tweak the way in which we cover our Flushing favorites. Last year we followed one team. This year our initial plan was for each of us to follow one player—for Steve, it would be David Wright; for Mike it would be Pedro—through his ups and downs of the 2006 season. But it’s a given that we would have focused on those guys anyway, and that would have left us repeating what we did last season. Wright and Pedro are our favorites, our Grant and Sherman (though neither has taken office as an inebriated president nor has either of them torched Atlanta—hell, they can’t even defeat a guy named Chipper yet alone the entire city). But what about the Jefferson Davises and the Braxton Braggs of the Mets? The guys we want to see secede from the club? The players who will have us throwing our cats at the TV and going John Wilkes Booth on our loved ones? Couldn’t we learn from the travails of Victor “The Human Base on Balls Machine” Zambrano? How about Kaz “I’ve Got Roger Cedano on Speed Dial” Matsui? Logic says no, we say yes.

Our plan is to write about the Mets 2006 season with a strict focus on the endeavors of four players, Wright and Zambrano (Steve) and Pedro and Kaz (Mike).

Join us as we figure out whether the upcoming season is a vintage merlot or a big bottle of backwash-filled thunderbird. And enjoy the new issue.

—Steve & Mike

23 More to Catch the Yanks! A White Sox World Series Game 2 Report by Jake Austen

A Bandwagon Jumper's Guide to the White Sox by Jake Austen

Now These Were The Real Idiots by Throm Sturmond

The Case For Jim Rice by Josh Rutledge

Willie Wilson: The Fatest Man Alive by Tim Hinely

1975-2005: 30 Years Since Tony C Retired by Frank D'Urso

Rain on Tin by Jackson Ellis

Mighty Casey by Peter Anderson

23 More to Catch the Yanks! A White Sox World Series Game 2 Report by Jake Austen

I can’t fucking believe I got to go to the World Series!

As a longtime Sox fan, I thought I’d seen it all. I saw Greg Luzinski hit a moonshot over old Comiskey’s roof. I was there when Yankees’ hurler Andy Hawkins threw a no hitter that the Sox won on a series of 9th inning errors. I witnessed a twenty-minute brawl with the Tigers that featured actual kung fu kicks. But nothing remotely prepared for the wonder that was Game 2 of the 2005 World Series.

The first good sign after taking my upper deck seat was that I didn’t see a different crowd than usual. Despite $140 face value tickets (and I will never reveal what I actually paid for my ticket), this seemed like a group of regular Polish sausage-fed Sox fans. Fathers with sons, buddies drinking beer, people on nacho runs…other than a statuesque blonde Astros fan in a sequined cowgirl suit, these looked like the same folks at a Tuesday Sox/Royals game in May. Except they were 30,000 more of them and they were all giddy.

On a personal note, the baseball fairies rewarded my decades of believing that the White Sox would make it to the World Series every year by putting in my hands a ticket that may have not seemed spectacular (6th row upper deck two-thirds down the third base line), but was in fact one of the best seats in the house. Though rain poured down the entire game, the direction of the wind and angle of the roof meant that despite everyone in the lower deck, in the right field upper deck, and in rows 1-5 of section 548 were getting drenched, I miraculously never got a drop of water on me. In contrast with the incredibly tense, dense, uncomfortable vibe of the stadium during the Jack McDowell-era ALCS game and the Jerry Manuel-era ALDS game I attended, it felt completely joyful and easy to be at the park for this game.

Words can’t capture the pandemonium in the seventh after Paul Konerko delivered his first pitch grand slam. With our team trailing by two in the World Series, our most popular player did, without hesitation, exactly what every single one of us was visualizing. As 41,432 people (minus Miss Texas) jumped and screamed for a full five minutes it was obvious that if this lead held we had just witnessed the single greatest moment in White Sox history!

One and a half innings later the Sox’ Baby Huey-esque closer Bobby Jenks blew the lead and the single greatest moment in White Sox history reverted back to whatever it had been before (Carlton Fisk telling Deion Sanders to “run out the ball, you piece of shit?” Disco Demolition?). Now we merely were seeing one of the best World Series games ever. A half-inning later when wee Scott Podsednik did what not a single one of us was visualizing I found myself incapable of jumps and screams. For a glorious post-walk off homerun eternity I merely shook my stunned head back and forth, an orgasmic smile tattooed on my face.

New to the World Series business, Sox management wasn’t sure what happens next, so they just let us stay in the stands as long as we wanted. On the field players did interviews, the Sox furry green mascot Southpaw begged Podsednik for a hand slap, and catcher A.J. Pierzynski brought out his wife and infant so a photographer could take a family portrait on the Sox’ victorious World Series field.

It was a good move by A.J. After a win like this it seemed unlikely that the Sox would have to return to their home field this year. Behind me a pair of pals who had purchased a $5,000 pair of un-refundable scalped Game 6 tickets were hooting and high five-ing. Perhaps when the beer wore off the financial ache might hit them. But then again, maybe not. Perhaps winning the World Series means the beer never wears off.

Jake Austen publishes Roctober magazine and helps produce the public access children's dance show Chic-A-Go-Go. He has been to hundreds of White Sox games, his favorite player is Ron Kittle and he was a left-handed catcher in college.

As a longtime Sox fan, I thought I’d seen it all. I saw Greg Luzinski hit a moonshot over old Comiskey’s roof. I was there when Yankees’ hurler Andy Hawkins threw a no hitter that the Sox won on a series of 9th inning errors. I witnessed a twenty-minute brawl with the Tigers that featured actual kung fu kicks. But nothing remotely prepared for the wonder that was Game 2 of the 2005 World Series.

The first good sign after taking my upper deck seat was that I didn’t see a different crowd than usual. Despite $140 face value tickets (and I will never reveal what I actually paid for my ticket), this seemed like a group of regular Polish sausage-fed Sox fans. Fathers with sons, buddies drinking beer, people on nacho runs…other than a statuesque blonde Astros fan in a sequined cowgirl suit, these looked like the same folks at a Tuesday Sox/Royals game in May. Except they were 30,000 more of them and they were all giddy.

On a personal note, the baseball fairies rewarded my decades of believing that the White Sox would make it to the World Series every year by putting in my hands a ticket that may have not seemed spectacular (6th row upper deck two-thirds down the third base line), but was in fact one of the best seats in the house. Though rain poured down the entire game, the direction of the wind and angle of the roof meant that despite everyone in the lower deck, in the right field upper deck, and in rows 1-5 of section 548 were getting drenched, I miraculously never got a drop of water on me. In contrast with the incredibly tense, dense, uncomfortable vibe of the stadium during the Jack McDowell-era ALCS game and the Jerry Manuel-era ALDS game I attended, it felt completely joyful and easy to be at the park for this game.

Words can’t capture the pandemonium in the seventh after Paul Konerko delivered his first pitch grand slam. With our team trailing by two in the World Series, our most popular player did, without hesitation, exactly what every single one of us was visualizing. As 41,432 people (minus Miss Texas) jumped and screamed for a full five minutes it was obvious that if this lead held we had just witnessed the single greatest moment in White Sox history!

One and a half innings later the Sox’ Baby Huey-esque closer Bobby Jenks blew the lead and the single greatest moment in White Sox history reverted back to whatever it had been before (Carlton Fisk telling Deion Sanders to “run out the ball, you piece of shit?” Disco Demolition?). Now we merely were seeing one of the best World Series games ever. A half-inning later when wee Scott Podsednik did what not a single one of us was visualizing I found myself incapable of jumps and screams. For a glorious post-walk off homerun eternity I merely shook my stunned head back and forth, an orgasmic smile tattooed on my face.

New to the World Series business, Sox management wasn’t sure what happens next, so they just let us stay in the stands as long as we wanted. On the field players did interviews, the Sox furry green mascot Southpaw begged Podsednik for a hand slap, and catcher A.J. Pierzynski brought out his wife and infant so a photographer could take a family portrait on the Sox’ victorious World Series field.

It was a good move by A.J. After a win like this it seemed unlikely that the Sox would have to return to their home field this year. Behind me a pair of pals who had purchased a $5,000 pair of un-refundable scalped Game 6 tickets were hooting and high five-ing. Perhaps when the beer wore off the financial ache might hit them. But then again, maybe not. Perhaps winning the World Series means the beer never wears off.

Jake Austen publishes Roctober magazine and helps produce the public access children's dance show Chic-A-Go-Go. He has been to hundreds of White Sox games, his favorite player is Ron Kittle and he was a left-handed catcher in college.

A Bandwagon Jumper's Guide to the White Sox by Jake Austen

As the mighty 2005 Sox returned to the World Series for the first time since the Eisenhower era, and won their first since World War I, volumes were being written about the spunky current team. But this is of minimal help for the inevitable bandwagon jumpers who until recently barely acknowledged that Chicago baseball was played south of Addison. If you want to come off as a real Sox fan you’ll need to connect with the convoluted, eccentric 104-year history of the Pale Hose, so hopefully these bullet points will help:

Sox FansAnyone who sat near the back rows of old Comiskey’s upper deck in the 70s recalls the Cheech and Chong-like clouds of smoke. Well, despite a long tradition of drunkenness and cannabis-abuse, Sox fans also pride themselves on being knowledgeable and attentive regardless of mental haziness. There are rare occasions when things get ugly (most notably when William Ligue attacked a Royals’ coach in 2002 for no reason, his arrest leading to U.S. Cellular’s nickname, “The Cell”). But generally a Sox game is fun for the whole family, and a great place for kids to learn new cuss words. Note that though all good Sox fans disdained Ligue’s crimes, historically we have been more forgiving, particularly to Shoeless Joe’s posse...

Black Sox

After Sox players conspired with gamblers to throw the World Series in 1919, South Siders continued to support their dishonest heroes, and a local jury gleefully exonerated them. They occasionally threw games en route to the 1920 World Series, for which they had virtually clinched a berth when the big boss, Charles Comiskey, ignored their day in court, and canned, then banned, the cheaters for life. To ensure the game’s integrity the owners appointed baseball’s first Commissioner, Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis. But don’t lionize Landis. A virulent racist, he blocked Bill Veeck’s 1943 purchase of the Phillies upon learning Veeck planned to stock his team with Negro Leaguers and break the color line.

Veeck

The one-legged man-of-the-people (his phone number was listed) will forever be the most beloved Sox owner. He was a populist who sat with the fans, dressed like a Joe, and was legendary for wacky stunts, like having the team play in shorts. And though he never had a midget bat for the White Sox (that was when he owned the Browns) he did once have Fantasy Island’s tiny Hervé Villechaize take batting practice. More importantly to Sox history, he introduced the exploding scoreboard with its pinwheels and fireworks, the only design element that made the trip across the street from old Comiskey to the new park, which by the way…

New Comiskey Park…no longer sucks. When first built its vomit-colored façade walls crowned by a blue UFO was as incongruous a design as the awful Soldier Field update. Being inside the steep upper deck was dizzying, and due to poor craftsmanship, the concrete walkways were cracking before the first All-Star break. Since then the team sold a bit of its soul (or rather its name, New Comiskey is now U.S. Cellular) to finance an overhaul that included removing the highest rows, replacing the spaceship with classy iron awnings, and designing an area where kids can take batting practice and race against a robot Scott Podsednik. The only thing they couldn’t bring back was Andy the Clown, who not long after being banned from appearing in costume at new Comiskey died a heartbroken clown.

Andy the Clown

Andy may be the key to understanding the heart of the Sox. For decades Andy Rozdilsky came to the games in a homemade clown suit. In a voice bordering on asthmatic, Andy led fans in the not-particularly-imaginative cheer “Leeeeeeeeet’s gooooooooooo Sooooooox!” His big trick was to give a pretty girl a flower but leave her with only the stem. He then had to get the stem back from her, as he only had one gag flower. What could represent the South Side better than a ragged, dependable, working class clown. The Sox current mascot, Southpaw, is far less distinctive, and not too funny. For humor these days fans need to look towards the dugout at…

Ozzie!

Ozzie Guillen has spent the last twenty years as a South Side icon. As 1985 Rookie of the Year he was immediately accepted by Sox fans because he continued a tradition started in the fifties with Chico Carrasquel and Luis Aparicio of stellar Sox shortstops from Venezuela (though the organist frequently played “Mexican Hat Dance” as his theme music, and his rooting section “Ozzie’s Amigos” wore Mexican sombreros, but hey, those countries are only 2,200 miles apart, who wouldn’t get them confused?). The speedy slap-hitter was a joy to watch, chattering with opposing baserunners and clowning for the fans. As a manager he’s continued the Chicago tradition of nepotism, as the first blockbuster deal of his reign was acquiring Freddy Garcia who was engaged to one of his in-laws. As a player he also had an in-law marrying teammate, Scott “Rad” Radinsky, who moonlighted in the punk rock band Ten Foot Pole. This unfortunately led to Scott recording a heartfelt ballad entitled “Third World Girl,” but that’s not Ozzie’s fault. Speaking of Rad…

Rockin’ SoxThe Sox are the rock ‘n’ roll baseball team. Cy Young winning pitcher Jack McDowell fancies himself a rocker and still tours with his band Stickfigure, though his National Anthem singing won’t make you forget Marvin Gaye. More impressive was Arthur Lee Maye, the self-described “Best Singing Athlete that Ever Lived” who played for the Sox in 1971, and had a healthy r&b career that included singing on Richard Berry’s original “Louie Louie.” More gloriously historical is the work of Nancy Faust, the Sox organist who was the first to play rock music at a baseball game, including the introduction of Steam’s “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye” to mock opposing players. More impressively she plays rock puns to introduce players (“In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” for Pete Incaviglia). Of course, more disastrously historical was the infamous…

Disco Demolition Night

On July 12, 1979 thousands of under-the-influence youthful South Siders stormed the field and harmlessly ran amok in the wake of a radio station publicity stunt gone awry, leading to a Sox forfeit. While many critics would point out this event’s negatives, including its subtext of racism and homophobia, and that because of it Steve Dahl is still on the radio, ultimately this mess was classic Sox. It had a dollop of Veeck absurdity, a hint of Ligue danger, and a whole lot of ragged South Siders not afraid to express themselves.

Sox FansAnyone who sat near the back rows of old Comiskey’s upper deck in the 70s recalls the Cheech and Chong-like clouds of smoke. Well, despite a long tradition of drunkenness and cannabis-abuse, Sox fans also pride themselves on being knowledgeable and attentive regardless of mental haziness. There are rare occasions when things get ugly (most notably when William Ligue attacked a Royals’ coach in 2002 for no reason, his arrest leading to U.S. Cellular’s nickname, “The Cell”). But generally a Sox game is fun for the whole family, and a great place for kids to learn new cuss words. Note that though all good Sox fans disdained Ligue’s crimes, historically we have been more forgiving, particularly to Shoeless Joe’s posse...

Black Sox

After Sox players conspired with gamblers to throw the World Series in 1919, South Siders continued to support their dishonest heroes, and a local jury gleefully exonerated them. They occasionally threw games en route to the 1920 World Series, for which they had virtually clinched a berth when the big boss, Charles Comiskey, ignored their day in court, and canned, then banned, the cheaters for life. To ensure the game’s integrity the owners appointed baseball’s first Commissioner, Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis. But don’t lionize Landis. A virulent racist, he blocked Bill Veeck’s 1943 purchase of the Phillies upon learning Veeck planned to stock his team with Negro Leaguers and break the color line.

Veeck

The one-legged man-of-the-people (his phone number was listed) will forever be the most beloved Sox owner. He was a populist who sat with the fans, dressed like a Joe, and was legendary for wacky stunts, like having the team play in shorts. And though he never had a midget bat for the White Sox (that was when he owned the Browns) he did once have Fantasy Island’s tiny Hervé Villechaize take batting practice. More importantly to Sox history, he introduced the exploding scoreboard with its pinwheels and fireworks, the only design element that made the trip across the street from old Comiskey to the new park, which by the way…

New Comiskey Park…no longer sucks. When first built its vomit-colored façade walls crowned by a blue UFO was as incongruous a design as the awful Soldier Field update. Being inside the steep upper deck was dizzying, and due to poor craftsmanship, the concrete walkways were cracking before the first All-Star break. Since then the team sold a bit of its soul (or rather its name, New Comiskey is now U.S. Cellular) to finance an overhaul that included removing the highest rows, replacing the spaceship with classy iron awnings, and designing an area where kids can take batting practice and race against a robot Scott Podsednik. The only thing they couldn’t bring back was Andy the Clown, who not long after being banned from appearing in costume at new Comiskey died a heartbroken clown.

Andy the Clown

Andy may be the key to understanding the heart of the Sox. For decades Andy Rozdilsky came to the games in a homemade clown suit. In a voice bordering on asthmatic, Andy led fans in the not-particularly-imaginative cheer “Leeeeeeeeet’s gooooooooooo Sooooooox!” His big trick was to give a pretty girl a flower but leave her with only the stem. He then had to get the stem back from her, as he only had one gag flower. What could represent the South Side better than a ragged, dependable, working class clown. The Sox current mascot, Southpaw, is far less distinctive, and not too funny. For humor these days fans need to look towards the dugout at…

Ozzie!

Ozzie Guillen has spent the last twenty years as a South Side icon. As 1985 Rookie of the Year he was immediately accepted by Sox fans because he continued a tradition started in the fifties with Chico Carrasquel and Luis Aparicio of stellar Sox shortstops from Venezuela (though the organist frequently played “Mexican Hat Dance” as his theme music, and his rooting section “Ozzie’s Amigos” wore Mexican sombreros, but hey, those countries are only 2,200 miles apart, who wouldn’t get them confused?). The speedy slap-hitter was a joy to watch, chattering with opposing baserunners and clowning for the fans. As a manager he’s continued the Chicago tradition of nepotism, as the first blockbuster deal of his reign was acquiring Freddy Garcia who was engaged to one of his in-laws. As a player he also had an in-law marrying teammate, Scott “Rad” Radinsky, who moonlighted in the punk rock band Ten Foot Pole. This unfortunately led to Scott recording a heartfelt ballad entitled “Third World Girl,” but that’s not Ozzie’s fault. Speaking of Rad…

Rockin’ SoxThe Sox are the rock ‘n’ roll baseball team. Cy Young winning pitcher Jack McDowell fancies himself a rocker and still tours with his band Stickfigure, though his National Anthem singing won’t make you forget Marvin Gaye. More impressive was Arthur Lee Maye, the self-described “Best Singing Athlete that Ever Lived” who played for the Sox in 1971, and had a healthy r&b career that included singing on Richard Berry’s original “Louie Louie.” More gloriously historical is the work of Nancy Faust, the Sox organist who was the first to play rock music at a baseball game, including the introduction of Steam’s “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye” to mock opposing players. More impressively she plays rock puns to introduce players (“In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” for Pete Incaviglia). Of course, more disastrously historical was the infamous…

Disco Demolition Night

On July 12, 1979 thousands of under-the-influence youthful South Siders stormed the field and harmlessly ran amok in the wake of a radio station publicity stunt gone awry, leading to a Sox forfeit. While many critics would point out this event’s negatives, including its subtext of racism and homophobia, and that because of it Steve Dahl is still on the radio, ultimately this mess was classic Sox. It had a dollop of Veeck absurdity, a hint of Ligue danger, and a whole lot of ragged South Siders not afraid to express themselves.

The Case For Jim Rice by Josh Rutledge

When word arrived that Jim Rice had once again been denied entrance to the Baseball Hall of Fame, I reached the immediate decision that some type of drastic protest was in order. Petitions weren’t going to cut it. Debate on Internet message boards was futile. Nothing less than a full-blown hunger strike could bring attention to an injustice of such an unprecedented severity. And in my case, I decided, the hunger strike was going to have to be a thirst strike.

Just as I have abstained from Wild Turkey bourbon for the past three years in protest against the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s failure to elect Twisted Sister front man Dee Snider, I knew I was going to have to give up a favorite beverage in support of Jim Rice.

So I resolved the following: I will not drink another drop of Coca-Cola until Jim Rice enters the Baseball Hall of Fame. And let the record show that I have no personal interest in Jim Rice. I am a diehard, blood-and-guts, religiously devoted fan of the Philadelphia Phillies. To have ever considered Jim Rice or any other non-Phillie a “favorite” player of mine would have been out of the question. But as a reasonable human being and a student of baseball, I’m shocked and appalled that the most dominant American Leaguer of his generation has been passed over for Hall of Fame induction 12 years in a row. And with Tony Gwynn and Cal Ripken Jr. on the ballot next year, it looks like Rice will have to wait until at least 2008 to finally receive his due enshrinement in Cooperstown. And Coca-Cola, who in recent years probably generated at least one percent of their annual profits strictly from my purchases, will have to get by without me.

It’s been reported in the press that Rice’s Hall of Fame snubbing may be “punishment” for the way he treated baseball writers during his career. By all accounts, Jim Rice was a dick. But so was Steve Carlton. As was Eddie Murray. The pundits argue that the likes of Murray and Carlton amassed such staggering numbers that their prickishness had to be overlooked. I would argue the same in favor of Rice. Murray finished with a .287 career batting average and a .476 slugging percentage. Rice, on the other hand, finished at .298 and .502.

Granted, Rice’s career longevity (or lack thereof) could be held against him, and 382 career home runs just doesn’t sound that great. But let us keep in mind that hitting 382 home runs in 16 years back in the 1970s and ’80s was probably comparable to hitting 500 home runs in that same time span today. And if longevity is a prerequisite for the Hall of Fame, then why is Kirby Puckett in the Hall? Shouldn’t the true measure of a player’s greatness be not how long he did it, but rather what he did? And if we measure what Rice did, the stats are awe-inspiring. In a 12-year run from 1975-86, he appeared in eight All-Star games and hit over .300 seven times. Six times he finished in the top ten in the AL in hitting, and four times he finished in the top five. In addition to winning three home run crowns, four other times he finished in the top ten in homers. In nine of those 12 years, he finished in the top ten in RBI. Seven times he finished in the top five. He led the league in total bases four times, and five times he finished in the top five in MVP voting. He became the first player in league history to amass 35 or more home runs and 200 or more hits in three consecutive seasons. And his monstrous 1978 season is still the stuff of legend. His 406 total bases that year were the most in the AL since 1937. He also led the league in hits, triples, home runs, extra base hits, and RBI – and was second in runs scored and third in batting average. His career .298 batting average was a remarkable achievement for a power hitter. Compare that to the career averages of Hall of Fame sluggers Mike Schmidt (.267), Harmon Killebrew (.256), and Reggie Jackson (.262). Mark McGwire, who may be inducted into the Hall next year, finished his career with a .263 average.

In this age of steroids, small parks, and watered-down pitching, it seems that baseball observers have become more and more obsessed with gaudy statistics. Five hundred career home runs was a ticket to immortality in a bygone era. But today, averaging 32 home runs a year for 16 seasons doesn’t seem like such a lofty standard. Players like Rice and Andre Dawson, who were great stars in their time, may be victims of this new infatuation with giant numbers. And that’s a shame. A player can only truly be measured by how brightly his star shone in his day. And if we’re talking the years 1975 through 1986, I’d be hard-pressed to name a single major league player who was greater, more consistent, or more feared by pitchers than Jim Rice. Just as importantly, I remember what it was like to be a little kid in the early 80s and hold a Jim Rice baseball card in my hand. Even if you didn’t particularly like Jim Rice, you wanted that card. You’d trade a George Foster and a Dave Kingman for it – because Jim Rice was money year after year. The numbers on the back of the card didn’t lie. And the picture on the front of that card – well, you thought maybe it would come to life and kick your ass if you didn’t pay it proper respect. Something tells me that little kids of this decade didn’t feel the same about an Edgar Martinez card.